Some high level definitions

KEY POWERFUL ENTITIES TO KNOW

Intellectual Property when it comes to plants, follows the standards and requirements from government or international agencies. In this article, we will refer to key institutions that determine how IP applies to plants.

- The USPTO (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office) defines and enforces the requirements and procedures through which Plant Patents and Utility Patents are delivered in the US.

- The USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture -PVPO) defines and enforces the requirements and procedures through which Plant Variety Protection Certificates are delivered in the US.

- The CFIA (Canadian Food Inspection Agency) defines and enforces the requirements and procedures through which Plant Breeders’ Rights (PBR) are delivered in Canada.

- The UPOV (Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants) defines the international standards for Plant Variety Protection in member countries. Plant Protection bodies/offices in member countries must follow UPOV’s guidelines and standards to obtain and maintain their membership. 75 countries are members of the UPOV, including the U.S. through the USPTO and the USDA (its Plant Variety Protection Office), Canada through the CFIA, and European countries. Hence, plant protection standards across those countries are rather consistent, but certainly not identical. The UPOV provides the contact information of the national agencies responsible for Plant Variety Protection in each member country (e.g. the Netherlands, Spain, etc.)

What is a VARIETY? a cultivar? a strain?

The goal of this article is not to be a glossary of hemp horticulture terms, so we’ll stick to high level definitions. Varieties usually occur in nature. The closest definition of a variety in hemp botanicals is probably “landrace”. Cultivars have by definition been cultivated/domesticated by mankind, selected, or bred. Strain, has traditionally been used in the community, but is however a term dedicated to microorganisms (e.g. bacteria or virus), not to the botanical world. For the purpose of this article, we’ll consider the term “cultivar” as the fittest…

A variety or cultivar is commonly defined by botanists as a group of plants within a single species (e.g. hemp) or sub-species that:

- can be distinguished from other plant groups of that same species by at least one characteristic, and

- can be reproduced unchanged into the next generation.

- is homogeneous in that all plants in the group look the same.

“For instance, most of us recognize that there are many different varieties of apples such as Granny Smith, McIntosh and Red Delicious. Although they are all the same species, each variety can be distinguished from the others by the fruit shape, size or colour and other similar types of characteristics.”

The CFIA, the USPTO and USDA, as well as the UPOV all refer to this definition of variety or cultivar.

Propagating materials

While the CFIA’s Plant Breeders Rights Act doesn’t make any distinction between the format of the propagating material to protect a cultivar, the following distinction is made in the US:

- The Plant Variety Protection Act, enforced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, through the Plant Variety Protection Office (PVPO), protects sexually reproduced (by seed) or tuber-propagated plant varieties.

- The Plant Patent Act, enforced by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, protects asexually reproduced (e.g., by cuttings, grafting and budding) plant varieties, which are not tubers. A Plant Patent is more demanding and costly to obtain than a Plant Variety Protection Certificate.

Both the Canadian Intellectual Property Office and the USPTO also accept applications and can deliver Utility Patents under their respective Patent Act. A Utility Patent can protect sexually reproducing plants and genetically engineered plants. Utility Patents are demanding and costly to acquire. In the botanical context, they are usually delivered to large Agri-Bio corporations in relation to GMO plants.

Patenting hemp plants

PRINCIPLES

Plant Variety Protection is a form of Intellectual Property rights that can be granted to plant breeders in order to protect their new varieties, like an inventor protects a new invention with a patent. With the grant of such rights for a new plant variety, a breeder obtains exclusive rights in relation to the propagating material of her/his variety or cultivar. At expiration of such rights, the creation falls into the public domain and can be used freely by third parties.

For instance, the CFIA says: “The holder is then able to protect the variety from exploitation by others and can take legal action against individuals or companies that are conducting acts, without permission, that are the exclusive rights of the holder.”

We could debate around the benefits of such rights and success of plant protection frameworks, but these are in theory intended to stimulate plant breeding and conservation.

The rights are only valid in countries where applied for and consequently granted. To obtain protection in other countries, an applicant must apply separately to the appropriate authority. An application originally filed in a member country of UPOV, may serve as a basis for claiming priority for a plant protection application filed in another UPOV member country. For instance, a breeder who obtained a PVP certificate in the US may claim priority for a PBR in Canada, for the same plant, and for plant protection in any other member country of UPOV. However, it doesn’t waive the need to apply for and obtain such protection in each country, while paying associated fees.

Eligibility requirements

A breeder of a new hemp cultivar can apply for plant protection. It may also be the breeder’s employer or “legal representative”. The applicant may be an individual, a company or an organization. Whether applying in the US or in Canada, you will generally be represented by a local IP agent or lawyer through the process if you do not reside int the country of application.

The owner of a cultivar can be granted a Plant Variety Protection (US) or Plant Breeder’s Rights (Canada) if it can be demonstrated that the variety is:

- New;

- Distinct;

- Uniform; and

- Stable.

What is “New”?

The cultivar may be sold for up to 1 year prior to the date the application, beyond 1 year, it is no longer considered new and therefore no longer eligible. The cultivar, may have been sold outside of the US or Canada for up to 4 years prior to the date of application within either of the country. If sold for more than 4 years in a foreign country, it is no longer eligible. Hence, in our context, the vast majority of identified “strains” are therefore in the public domain and no longer eligible, in theory…

What is “Distinct”?

A cultivar must be measurably different from all varieties of common knowledge which are known to exist at the time the application was filed. A variety of common knowledge includes a variety already being cultivated or exploited for commercial purposes or a variety described in a publication that is available to the public. While this requirement makes any landrace variety obviously ineligible for protection (e.g. PVP, PBR or Plant Patent), it is of key importance to breeders, as many of the “hybrid strains” currently available may be sitting in a grey area.

What is “Uniform”?

A cultivar must be sufficiently uniform in its relevant characteristics, subject to the variation that can arise from the method of propagation. However, variation should be predictable to the extent that it can be described by the breeder, and should be commercially acceptable. This is also a material criterion that is usually uneasy to answer with hemp cultivars, where few true breeding / stabilized lines actually exist.

What is “Stable”?

A cultivar must remain true to its description over successive generations. The key characteristics of the cultivar, used to support the plant protection application, must remain stable through several generations of seed or clone propagation.

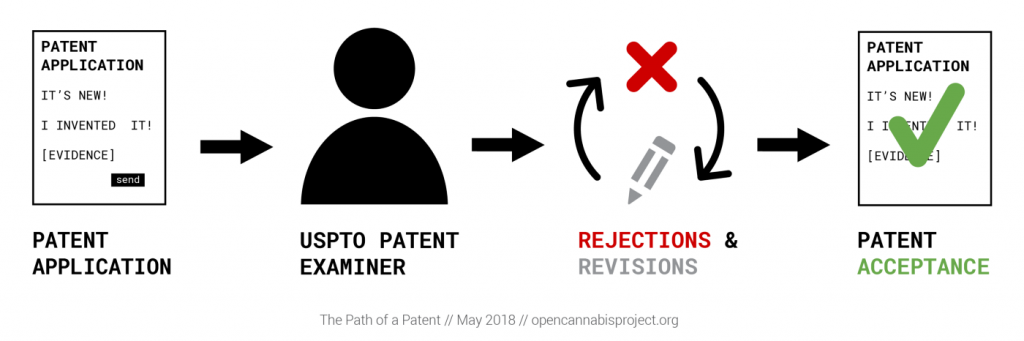

APPLICATION PROCESS

Breeders considering formally protecting their cultivars should follow processes described below:

The costs associated with a PBR or PVP are more affordable than those of a Plant Patent (US only) and Utility Patents. The range is $2,000-$2,500 for filing an application, leading to a total of $5,000-$10,000+ including annual fees throughout the full duration of the protection (up to 20 years).

The costs associated with obtaining a Plant or Utility Patent start at $5,000 for filing an application, usually leading to a total cost of tens of thousands of dollars throughout the entire duration of the protection.

Limitations TO THE RIGHTS

There can be a few, but sometimes material, exceptions to the rights of breeders who obtained a protection on their “strain”. This is where we can observe significant differences from a country to another. In the US, a PVP Certificate gives its holder more control on the distribution and propagation of her/his cultivar, leaving fewer options to third parties to use and abuse the “strain”. In Canada, PBRs can be slightly more constraining on the holder. Below is a non-exhaustive list of possible exceptions depending on the country:

- When for private and non-commercial purposes, a third party may grow and propagate the protected cultivar

- For experimental purposes, protected varieties may be used in research

- Protected varieties may be used for breeding and developing new plant varieties according to the Canadian PBR (!)

- Note that, certain national plant protection acts (including the Canadian PBR) can feature mechanisms to ensure that protection holders (breeders) make the protected cultivar available to the public at reasonable prices, widely distributed, that reproductive material of high quality is available…

Finally, revocation, annulation or cancellation of exclusive rights is possible in Canada and the US under certain specific conditions which can be and do not limit to:

- the variety was not distinct, uniform or stable when rights were granted;

- the variety was sold prior to application in contradiction with applicable plant protection act

- the holder was not entitled to the grant of rights

- the holder failed to pay the annual renewal fee

- the holder was unable to supply propagating material of the variety

- the holder was unable to prove that the variety was being maintained

- the holder failed to comply to a request to change the denomination

- the variety is no longer uniform or stable

Denomination and Trademarks

According to the UPOV standards, obtaining a PVP Certificate or PBR for your cultivar also protects its denomination/name for the same duration. “The breeder may also take action to prevent another individual or company from using the approved denomination (name) of their protected cultivar when that individual or company is selling propagating material of another cultivar of the same genus or species”. Note that is generally impossible to trademark a cultivar denomination (read “strain name”) if it has obtained plant protection or is already in the public domain.

However, it is in theory possible to trademark a “strain name” for commercial use, provided that such name is different from the denomination in the PBR, PVP or Plant Patent (e.g. PVP for cultivar “XH-A5506” with trademark for brand “MediCannaPharma”…). Trademark prevents other businesses from using the trademark name (e.g. for merchandising). This indeed comes at additional costs.

CONCLUSION

While we did want to cover the topic of “hemp strain patenting” in this article, breeders remain the sole decision-makers when it comes to protecting their creations. In theory, the vast majority of existing cultivars is in the public domain and not eligible for plant protection (e.g. PVP, PBR or Plant Patent) for the simple reason that they have been available to the public for more than a year (i.e. they are not new). In such cases, breeders should still make sure that their cultivars are known in the public domain in order to prevent any third-party from “patenting” their own creation (i.e. an overreaching PVP, PBR or Plant Patent).

The USPTO, PVPO and CFIA consult the data available on public domain creations prior to allowing plant protection on a cultivar. Breeders with cultivars who believe are eligible for plant protection may decide that their creations are worth putting the money and efforts to obtain a PVP, a PBR or a Plant Patent (potentially in various countries). PVP Certificates and PBRs imply spending several thousands of dollars to obtain and maintain associated “exclusive rights”. The cost is even higher for Plant or Utility Patents.

And by the way… PVP Certificates or PBRs do not give you protection on themselves, you need to enforce them. That means that obtaining a PBR or PVP Certificate, is actually an authorization to spend more time, money and efforts to track, demonstrate and fight if/when someone used your cultivar without your prior consent. We quickly see that this is not a practical nor sustainable approach for many breeders. Add the potential obligations that come with some of these rights and you are probably already looking for another way…

That’s where it becomes interesting. Once you know what it takes to obtain a protection/exclusive rights on a plant variety or cultivar, you can take precautions to avoid someone to steal your creation and “put a patent on it”, in order to later harvest the fruits of your passion and skills. Keep this article in your favorites, come back to it as many times as you need to develop your strategy to protecting biodiversity.

How do I make my strains known in the public domain?… read Part 2 !

Very good to see that going on and I live in Brazil where there isnt anything done yet to improve our rights to do what me as a breeder and brazilian growers. I would like to have some support here but there isnt any unfortunately

Thanks Luiz for your comment.